Her Cookbook Introduced Middle Eastern Cuisine To The West. She Got One Of The Main Recipes Wrong.

A tabouli mystery, solved.

My father had a housekeeper named Marina, who lived with us when I was growing up, and she was, in a very real sense, a part of my family. She passed away from cancer in 2005 at home in the Philippines, and I remember speaking to her on the phone a few days before she died. I told her that I loved her, and she told me that she loved me, and we cried, and then I said, “Talk soon,” even though we both knew that wouldn’t happen, and she said, “Talk soon, tabouli1 boy.”

“Tabouli Boy” was the affectionate nickname she had called me since I was 3 years old. I love tabouli, and I have loved it forever. The best tabouli ever made was Marina’s. When I was just a toddler, I would spend hours sitting with her in the kitchen, watching her make tabouli.

My parents separated in 1991, and my siblings and I moved with my mother to Idaho. But for the next decade, I would return to LA to stay with my dad for summers and holidays, and in the times between, I would call my father’s house and chat with Marina from time to time.

I was very upset about my parent’s divorce, and the tabouli became something I sort of projected my feelings on. My mother tried hard to make tabouli the way Marina had, but I would invariably hate it. This was upsetting for my mom for a number of reasons, but one of them was that she was the person who had told Marina about tabouli in the first place. Marina had taken my mom’s recipe and made it her own, and that was the one I loved.

So, every few months, my mom would try to make tabouli, and since I was a depressed child, I did not hide my dissatisfaction with her attempts. I also couldn’t articulate what was wrong with it. I had watched both of them make it so many times, but I was a child, and the ingredients all looked the same. Making the matter more confusing, I could not find a tabouli version like Marina’s in Idaho. You could buy “tabouli” at the grocery store or at certain restaurants, but it was like my mother’s.

Some members of my family became convinced that this was all in my head. The taboulis were the same, and I was just psychologically favoring one over the other. It’s a theory that I even found compelling for a while.

When I was 23, my mother had surgery, and I was unemployed, so I flew back to Idaho to spend the month with her. We couldn't do much, but we could putz around the kitchen, and for the first time in a decade, we decided to try our hand at tabouli. I was older now and could articulate the differences better than before, and after a few weeks of trying different portions, we came up with something that was a close approximation of Marina’s tabouli.

The short answer is this: there had been too much bulgur in my mom’s version.

But most of the recipes I could find for tabouli online also seemed to make this mistake. The ubiquitous Near East boxed tabouli on every grocery shelf in America has that version on the back. It’s basically a bulgur salad with some parsley, tomato, and onions. Marina’s version is a parsley salad, with tomato, onions, and some bulgur.

Had Marina invented this heavenly version herself? Well, maybe, but probably not. She probably just had been to a Lebanese restaraunt.

In retrospect, the problem with our attempts in the 90s to figure all of this out is that it happened in lily-white Idaho. I had never been to an actual Syrian or Lebanese restaurant. If I had just gone to one, I would have saved myself a lot of time. The authentic version of tabouli is much more green. It’s not the exact same as Marina’s but it solves the main problem of too much bulgur.

Why does tabouli in the West have too much bulgur?

A few years ago, I decided to find out. I called the Near East company. They wouldn’t talk to me about the history of the recipe. I bought the out-of-print memoir by the woman who founded the Near East company 60 years ago. It does not mention tabouli. I called a number of food authors trying to figure out the provenance of the common western tabouli recipe. No one knew for sure, but one had a lead: Claudia Roden.

An Egyptian Jew of Syrian descent, Roden’s family moved to London after the Suez crisis. She brought along her family recipes and an enduring fondness for the food of her childhood. She spent over a decade gathering recipes from the region.

“I became like a collector,” Roden wrote in 2015. “I wanted to know how the Iranians cooked, how the Iraqis cooked. I would go to the Iranian embassy and people would say, "Have you come for a visa?" And I would say, "No, I’ve come for recipes!"

In 1968, she published the first edition of A Book of Middle Eastern Food. This seminal cookbook is generally credited with introducing Middle Eastern cuisine to the United Kingdom and the United States.

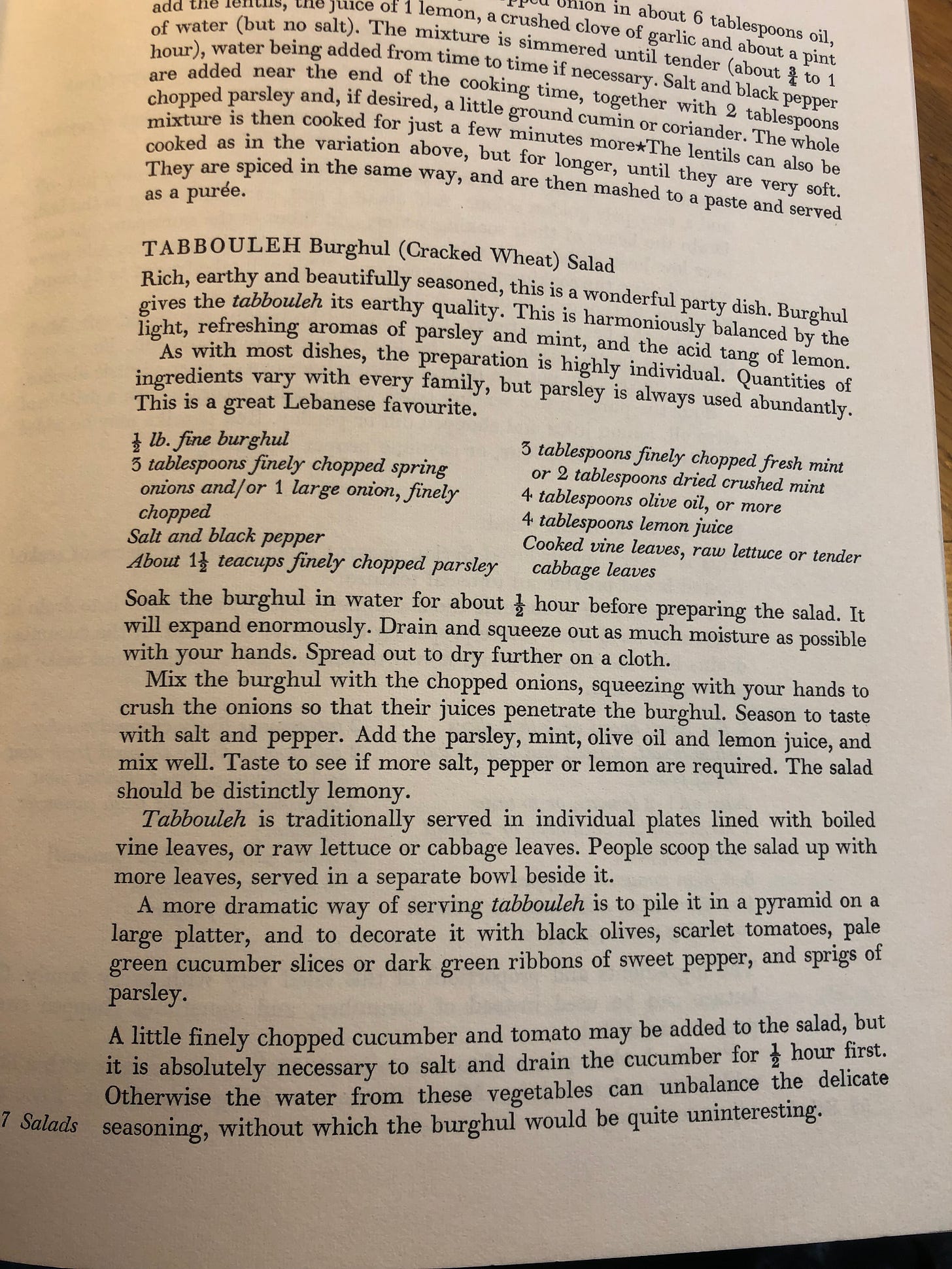

No offense to Roden, but the mystery of why tabouli in America tastes terrible begins with this book. The original version is out of print, but a copy is in the New York Public Library. If you give them some notice, they’ll bring it from the catacombs and let you read it in their research room. It has the bad recipe for tabouli.

After trying and failing to get in touch with Roden, one food writer told me they vaguely recalled her addressing the tabouli in a follow-up version of the book.

Indeed, in the updated 2000 version (The New Book of Middle Eastern Food), Roden included a note before her tabouli recipe.

“When the first edition of this book came out, I received letters,” Roden writes, “telling me that I had too much bulgur in that recipe.”

BOOM.

“One letter from Syria explained that mine was the way people made the salad many years ago, when they needed to fill their stomachs. You see, many of my relatives left Syria for Egypt a hundred years ago, and that was how they continued to make it. The following is the contemporary version.”

Her updated recipe is not the exact same as Marina’s. It calls for “salt and pepper” and not Marina’s cayenne pepper. (Cayenne peppers come from South America.) In fact, once, when I was proudly sharing Marina’s recipe for “the best tabouli in the world,” some people from the Middle East took umbrage at my inclusion of cayenne pepper. Fair point!

Over the years, my version of Marina’s tabouli has evolved to the point where I occasionally include no bulgur, making it simply a parsley salad. I also sometimes include totally non-tabouli elements like diced bell peppers and celery.

Roden’s updated version calls for only flat-leaf parsley, but Marina thought, and I agree, that half flat-leaf and half curly actually provide a better crunch.

Which is to say, my tabouli is not really tabouli at all, though it is a descendent of it, garbled through Syrians who moved to Egypt, a British cookbook author, a West Virginian mother, a Filipino cook, and a secular Jew who was raised in Idaho.

And it’s great!

Recipes evolve. They begin in one place and end up in another place and between those two places are a million other places where a million other people tinkered with them a million different times. There are some thoughtful versions of the “cultural appropriation of food” argument—I don’t find them very convicing but they aren’t totally unhinged— but social media is filled with people making unhinged versions of the argument, which basically involves them getting mad at some white dude in St. Paul for selling Enchiladas with moose meat, or something.

The reason every version rubs so many people the wrong way is that my experience with tabouli is not unique. Every family has stories like this. Grandma’s goulash recipe is actually just a cheap bolognese. But it’s your goulash.

You can go too far with this! You can commit what might be called food imperialism (lol). Want an example? Here’s an example.

SEVERAL years ago, shortly after San Yan Wong, a recent arrival from Hong Kong, opened his Hunan Garden Restaurant on Mott Street in Chinatown, a customer came in, sat down and ordered chow mein. Mr. Wong, who is also his own head chef, remembers that he whipped up a platterful of stir-fried soft noodles covered with shredded pork, sliced bamboo shoots and bok choy, fresh water chestnuts, snow peas and Chinese black mushrooms, and sent the dish out of the kitchen. Minutes later he was called to the customer's table.

''What's that?'' the customer asked. ''Chow mein,'' Mr. Wong said. ''That's lo mein, not chow mein,'' the man insisted, and he began to describe in detail that preparation so dear to generations of Americans: vegetables, stir-fried to softness, sitting atop a mound of dry-fried noodles and rice, and topped with a few julienned slices of pork. Mr. Wong, a man who likes to please his customers, listened carefully and, within days, chow mein American style was added to his menu. ''I felt that if I did not have it, if I told people I would not make it, they would leave,'' he said.

Mr. Wong, who is originally from Shanghai, said he used to try to educate non-Chinese by serving perfectly authentic Chinese food. But now he has decided that in many cases ''it is best to give them what they wish.'' He said that what Americans refer to as lo mein is chow mein to the Chinese and what is chow mein to Americans does not exist in China.

It’s not bad that stupid New Yorkers invented some disgutsing dish and want to order it. That’s fine. What I do think is ridiculous is that they took the name of a real well-known famous dish and then told the Chinese chefs to rename the authentic one! Call your own dish whatever you want, but don’t tell other people to call it that too. It makes it very confusing ordering chinese food in NYC!

I’m sure that actual Lebanese restraunts occasionally get complaints from people who are like, “not enough bulgur.” Sorry, buddy, they’re making it right.

I call my tabouli-inspired dish tabouli because it’s my tabouli but it would be rather silly for me to expect a Syrian restaraunt to add cayenne to their tabouli.

My tabouli owes itself to the cuisine of the Levant and a pepper from South America, but most importantly, it is the creation of my family. It’s Marina’s Tabouli.

And it’s the most delicious thing in the entire world.

Here’s the recipe: